Learning how to play a game from AI

Teaching an AI to play L'oaf and seeing what a human can learn from it.

I recently got the board game L'oaf as a gift from a family member. Yesterday I first sat down to play it and had a blast. For some reason though, I keep thinking "could I make an AI that would be unbeatable at this game?" whenever I play moderately simple strategy games like this. I also had this feeling playing Hanamikoji, but someone else already did what I dreamt of so I lost some motivation.

Before I get into the details, let me state that I will not be sharing a playable version of my digital recreation of the game out of respect to the creators of the game. If you want to play the game, go out and buy it! (Although, I am considering emailing the creators of the game to see if they will let me make a CLI-version where you can play against the AI)

Since it’s likely you haven’t played the game yet, here’s a brief rundown on what it’s like: each round, everyone secretly plays a numbered work card (0–11) and you add them up to see if the bakery hits the day’s order. If the team succeeds, the player who worked the hardest gains reputation based on how far their card sits above the round’s printed average. If the team fails, the laziest player loses reputation by that same average-based difference. Then, at the end of the round, you add on an evaluation effect that depends on success or failure. These evaluations can target specifically players that are the lowest, highest, have a good or bad reputation, and can move them up or down. When 5 cards fail or pass, the game is over. The person who has the most points in their hand at the end of the game wins, with a little bonus for the reputation you achieved. If you're in the negatives you get fired and automatically lose. You spend the whole game trying to do as little work as possible, while also keeping a positive reputation to not get fired.

I started by recreating the game in Python. The manual labor involved (hopefully) correctly interpreting the rules and copying over the cards into a JSON format. Then, I made the game by recreating the logic of each round and writing out the win/lose conditions.

L’oaf is an optimization problem disguised as a modern-time workplace joke - you want to win while doing as little work as possible, and you want your opponent to overcommit at the wrong time. One important strategical detail is ordering: the baseline reputation move happens first, then the evaluation effect checks its condition and applies bonuses or penalties. That means a carefully chosen play can move you (or your opponent) across a condition boundary, or even swap who counts as lowest or highest at the moment the evaluation resolves, provided you can predict what the other side is likely to spend.

Now I wanted to train an AI to get good at this game. An interesting point of knowledge is that modern chess engines did not reach their current level by studying a big pile of human games; AlphaZero started from random play, only knowing the rules, and improved through reinforcement learning from games against itself. This is called self-play. If the agent becomes strong, I can then treat it as a guide: inspect when the computer plays lazy, when it puts in effort, and which evaluation flips it tries to engineer several rounds in advance.

The training process consists of reinforcement learning with self-play data collection. The agent is a neural network policy that sees a compact representation of the public game state: what is the remaining hand? What is the current reputation? How many cards are on the bad and good boss pile? What is the current round evaluation effects, and what is the currently visible round requirement? The AI then outputs a probability over the 12 work cards. Since you can only play cards you still have, the action space is masked so illegal moves are impossible.

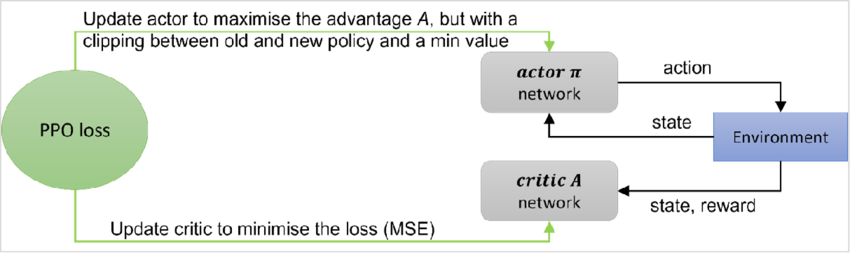

The learning algorithm is PPO - Proximal Policy Optimization combined with self-play. Concretely, I let the computer play many games against an opponent, records trajectories of what it saw (the state), what it played (the action), and how the game ended (win, loss, draw). From that data it updates a policy network, which is the part that outputs a probability distribution over legal moves. Moves that tend to lead to better outcomes get nudged up in probability, and moves that tend to lead to worse outcomes get nudged down. (If you want to learn about PPO, the algorithm that is also behind training of many LLMs, I recommend this article by Chris Hughes).

In parallel it trains a value function (the critic), which takes the same position and predicts the expected final result from there, essentially how good the position is if you keep playing the current strategy. PPO uses that value prediction to compute an advantage signal: did this move do better or worse than the value function expected? Finally, PPO limits how much the policy is allowed to shift per update, so learning stays stable and does not collapse from one batch.

Tournaments and learning

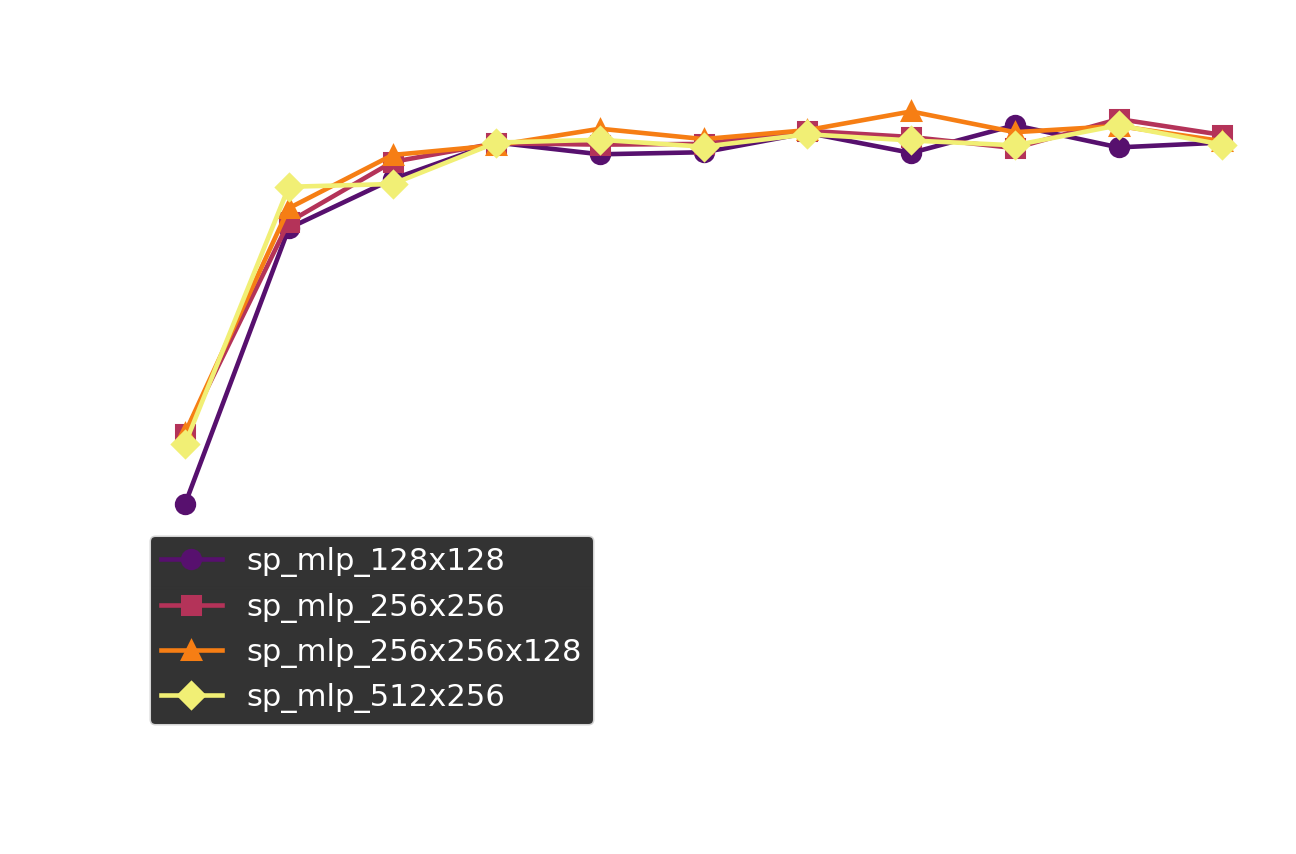

Since I didn't know what size network would be necessary to get good at L'oaf, I created the following networks: 128x128, 256x256, 256x256x128, and 512x256. For fun, I decided to let these networks play 10000 games against each other and determine their win/draw/lose rates, as well as an Elo ranking. My hypothesis is generally that the largest network can be the best, but it usually requires most learning to get there, and can provide no benefit over a smaller network if it already can play pretty much optimally. The results of the tournament can be seen below!

Since we have three outcomes and the networks are relatively well-matched, most win rates hover around 1/3. To make it a bit better to understand how strong all these self-trained networks are, I added a baseline of random moves and a simple heuristic model that I let ChatGPT come up with. Both of these get demolished by the trained networks. To figure out which network is the strongest, I used Elo as a metric. Every network started at 1000, and their Elo is updated every game based on both agents' current Elo and the game outcome. Of course this is a crude metric (order of matchup matters, the baseline_random model can be good/bad vs some opponents, etc), but it gives a result nonetheless.

To my surprise, the 128x128 network wins out! It seems the problem is simple enough that a good solution can be found in a relatively small network. One way to check if the bigger networks just needed more time to train, is by looking at the progress they are making during training. An easy to interpret metric is the win rate the model has versus the older versions of the model it is playing against. I simulated 1000 games of the last model versus the older models.

All models appear to have pretty much reached a stable point, at >80% winrate against the older models. Interestingly, the model that ended up with the highest Elo rating - 128x128 -, is also the one that seemingly improved slowest during training. I don't know if this has any meaning in it, but it is an interesting coincidence.

How different are the AIs?

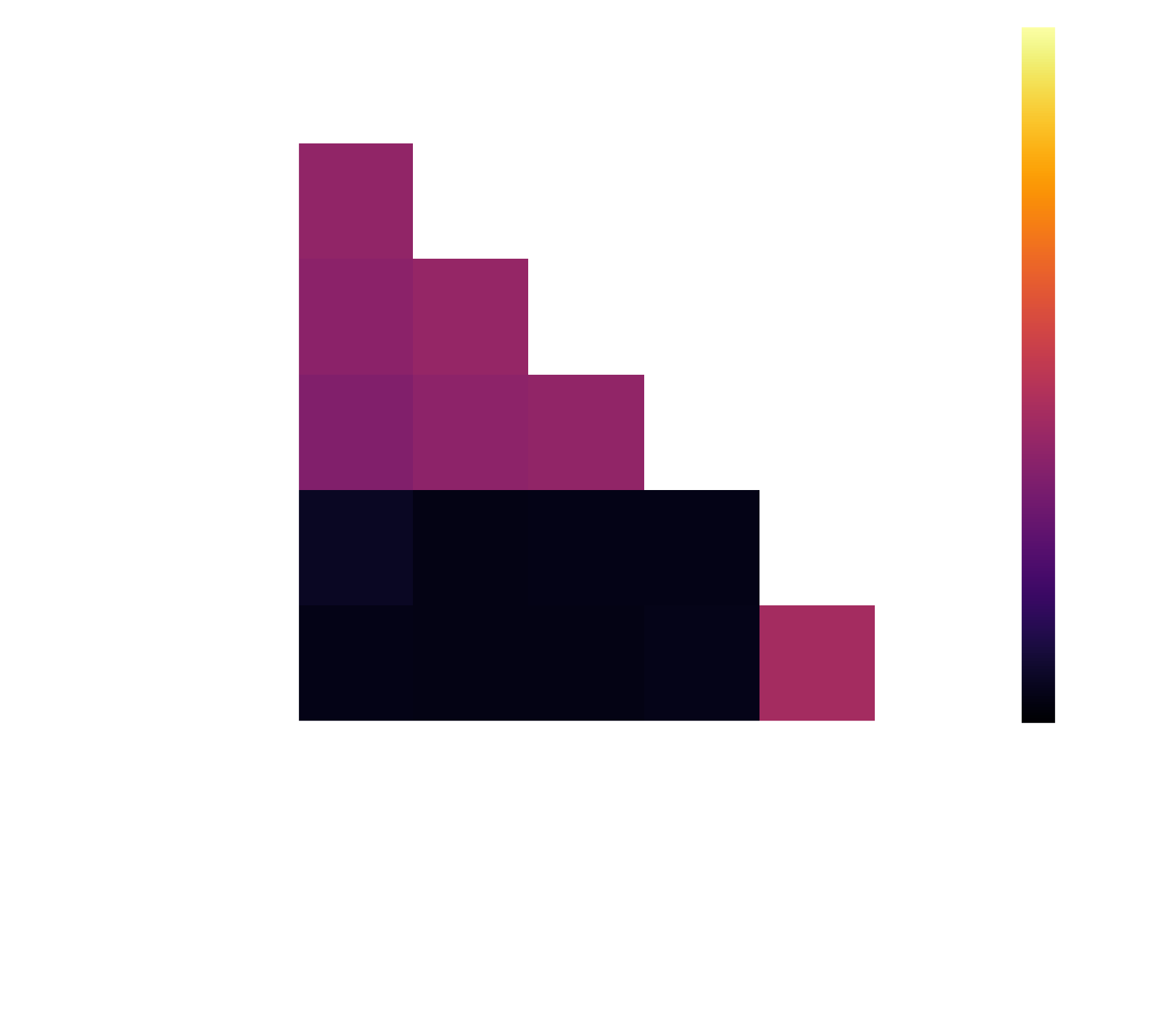

Even though the Elo ratings differ at the end of training, that does not automatically mean the agents play in meaningfully different ways. Each policy network takes the current game observation and outputs a probability distribution over the 12 work cards. During self-play I usually let the policy sample from that distribution, which adds some randomness and helps exploration. For a comparison between networks, randomness gets in the way, so in the analysis step I treat each network as deterministic by taking its single highest-probability move (the argmax of its action probabilities).

To build the comparison set, I did not hand-pick scenarios. I ran many simulated episodes and recorded every decision point as a pair: the observation vector plus the action mask at that moment. Each episode selects a driver model at random, plays against a fixed opponent model, and occasionally forces a random legal action (epsilon) to increase coverage of the state space (in total >18000 states). This matters because fully random states can include impossible combinations of hands, deck, and card faces. Trajectory-collected states stay reachable under the rules and stay close to the kinds of situations the agents actually encounter.

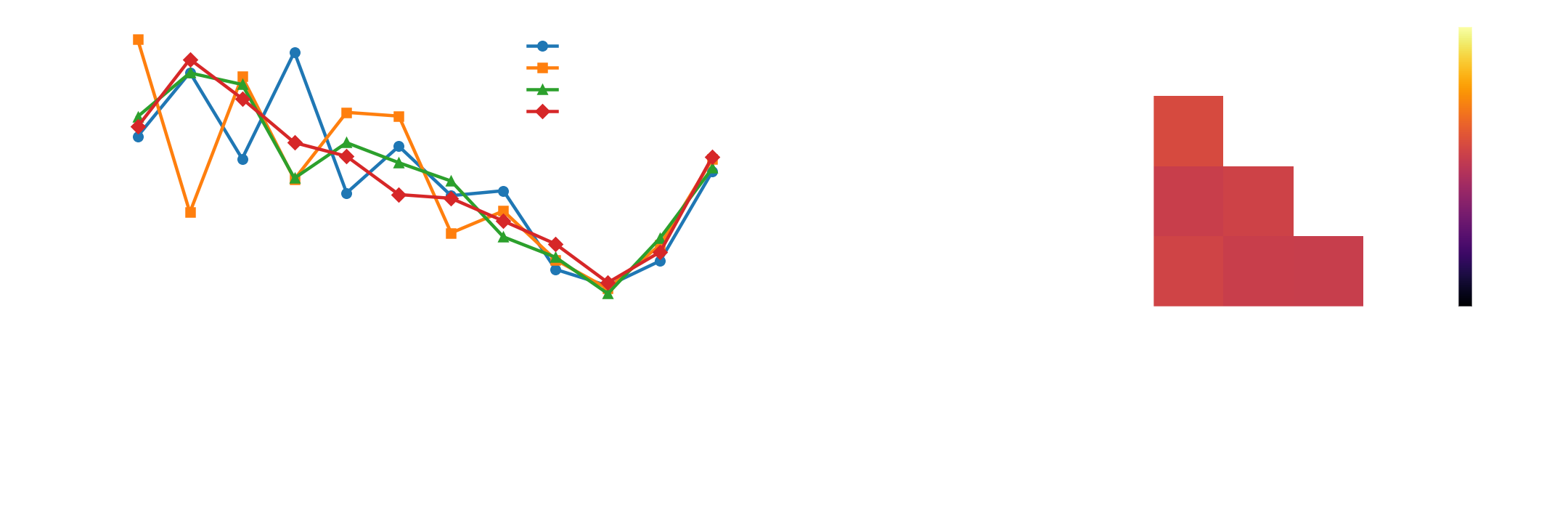

For each state, I extract (1) the argmax action and (2) the probability assigned to that argmax, which is a rough confidence score that the network has in the move. Agreement between two models is simply the fraction of states where their argmax actions match. Plotting this as an agreement matrix shows whether the policies are practically the same with different Elo noise, or whether they diverge systematically. You could even continue this line of work to look at where the networks differ in move, to study what the break-points are.

Clearly, the networks differ a lot on strategy, as they overall only have ~0.6 agreement and all have their own quirks (256x256 dislikes playing 1, 128x128 likes playing 3, etc). On top of this, they also have quite different moves they play, except for myseriously all nearly completely avoiding 9. I interpret this as the game L'oaf having a lot of ways to win, as there is substantial randomness in the outcome of the game (which we can glean from that all these strategies have nearly equal win rates).

Can we learn from the AI?

Black-box AI is a big topic, and figuring out how to make it interpretable is a considerably large research direction. We can already learn something from the statistics approach above - i.e., focus on playing low cards first or if you have to go high play 11, avoid 6-9. However, this is quite shallow, as we still don't know when to play which card. A practical way to get a foothold is to try “model distillation”: train a simpler, white-box model to imitate a stronger black-box model’s decisions. The imitation model is not trained on win or loss directly, but it is trained to copy what the teacher would do in the same situation. Then we hope that the imitation model gets close enough to the black-box model to learn what it is doing.

In my case, I took the best-performing PPO policy network (128x128) and generated a dataset of game states from self-play. For each state, I asked the PPO model what it would play (deterministic argmax, with legal-move masking), then trained a shallow decision tree (an interpretable model) on hand-crafted features that describe the state in human terms. A full 12-way classifier would still be too detailed to interpret, so I simplified the target: instead of predicting the exact card, the tree predicts a tier. The tiers are relative to your current hand: play a low card, play a middle card, or play a high card. This gives a first-pass, readable policy.

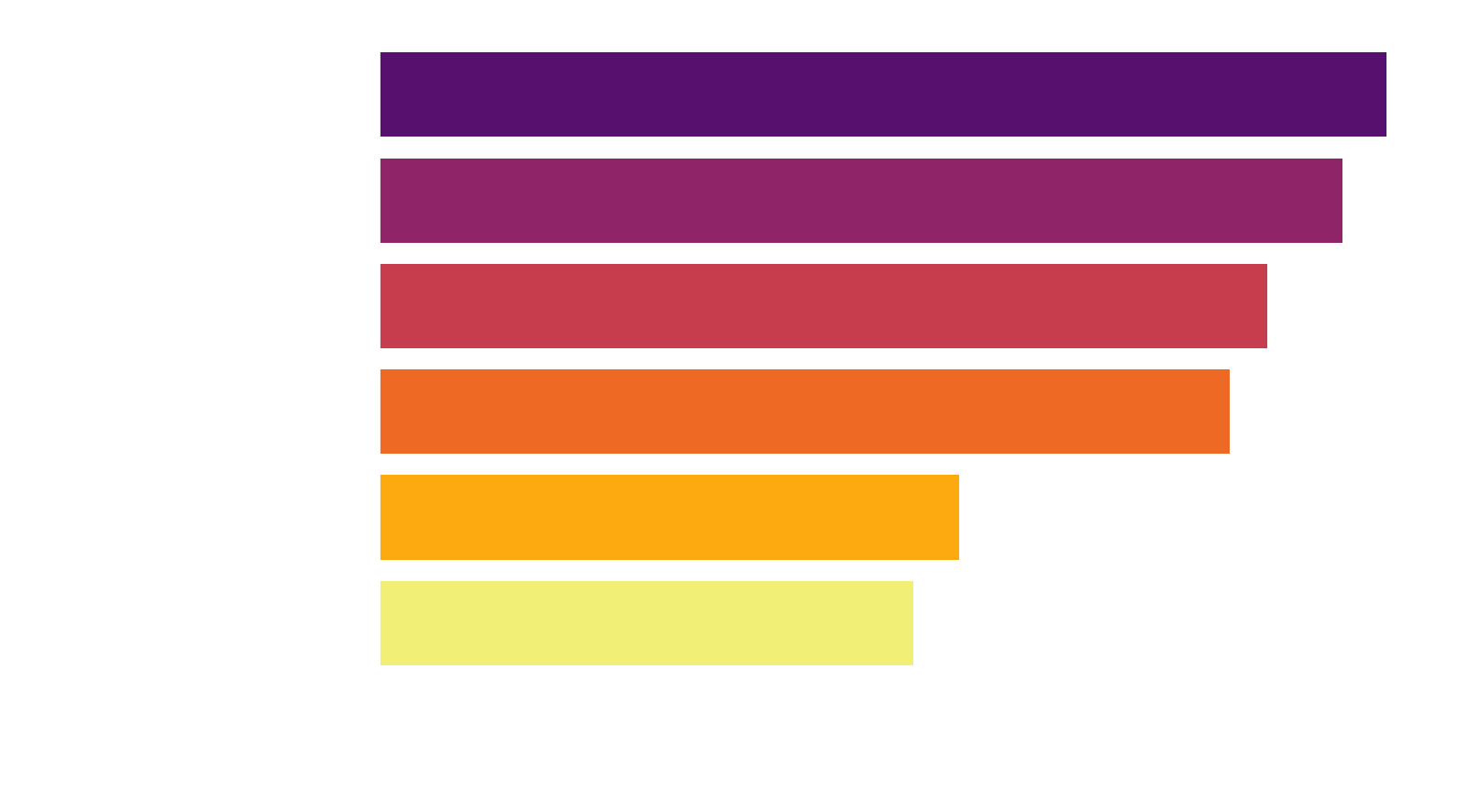

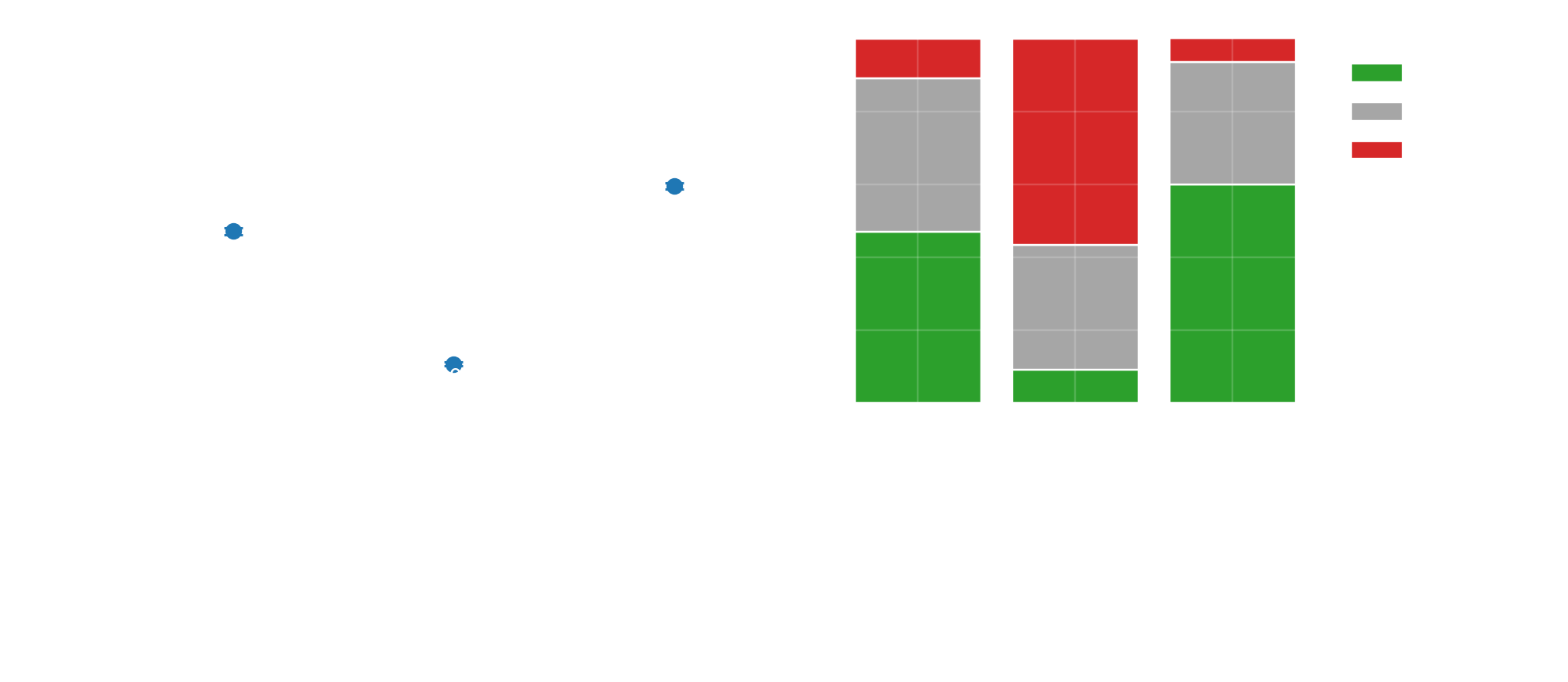

Let's see how the new imitation model baseline_tier_tree_128 performs first in the tournament setting. Clearly, we expect lower performance than the best models. Unfortunately, the imitation model is only a fraction as strong as the fully trained models, landing between the random baseline and weakest trained model. There is a common problem here: the more we push the model to interpretability, the more performance we usually lose.

To interpret what the imitation model is doing, we can examine the decision tree which only consists of readable rules. Nonetheless, it's still quite hard for a human to understand, in part due to the code-language used, but this could be used to make a flowchart we understand. On top of this, it often uses exact numeric cutoffs that would never be practical in play, so we'd have to reduce the imitation network even further to simpler (hard-coded?) rules that you could apply on the fly for it to be useful. I spent some time reading what the major branches of the decision tree are and was able to "human-distill" it back to a few rules that were at the level I could use in a real game:

1: Default is to play small (conserve points).

As long as the effect of a round is not “the lowest reputation player is affected after a pass”, the tree almost always chooses your smallest remaining card, across most reputation and target-average settings. This is the dominant behavior in the largest branch of the tree.

2: If your reputation is negative and the round target average is low, spend big to stabilize.

When your reputation is negative and the target average per player is 4.5 or lower, the tree often switches to your largest remaining card (especially if your remaining cards are all fairly high already).

3: When a fail is heavily punished, play middle cards more often.

If the effect of a round is “the lowest reputation player is affected after a pass” and the reputation change after a fail is very negative (around -1.5 or worse), the tree prefers a middle card rather than the smallest.

4: In high-average rounds, prefer middle cards.

When the target average per player is above ~6.5, the tree leans strongly toward middle card choices (with a few “still play small” exceptions when other conditions make passing easy).

I checked how often these heuristics agree with the full decision tree to see if they faithfully represent the imitation model. As it turns out, 78% of the time these 4 simple rules will give you the same result as the imitation model. I also compared the 4 simple rules to the full network and random play, which you can see below. It's actually not bad, winning nearly half of the time versus random, and hardly ever losing. It comes close to the distilled network vs random, but is a lot worse against the distilled network itself.

If you want to play with the decision tree, you can take a look at the HTML insert. Take note that these are compressed rules of a compressed network, so they are probably in practice not all that amazing (compared to the full networks, at least, they might still beat your friends.